Part 82: Détente

Chapter 2 - Détente - 1836 to 1840Al Andalus in 1836:

Al Andalus has a long and storied history, one that dates all the way back to the eighth century. At the frontier of Islam and the edge of the world, it led the early wars against Christian Europe, it launched the first explorations into the vast western oceans, it discovered and conquered the great continents of Gharbia. A blossoming of culture and trade quickly followed, but this golden age came to an end with the Fitna of al-Andalus, an era of fractious civil war in Iberia. Al Andalus weathered through it to reunite, however, and now stands ready to retake its place amongst the Great Powers.

And throughout all that time, almost eight hundred years of history, the rich and vibrant city of Qadis has stood tall and strong.

Having never fallen to an enemy invader, Qadis surpassed its competitors to become the largest city in Europe by 1836, with its working population nearing 350,000 people.

The population of Al Andalus as a whole is estimated to be 14.2 million, with its working population numbering 3.5 million. Of this, the vast majority are Sunni Andalusi, with our largest minority being the Shiite Andalusi in Granada and the Catholic Portuguese in the northwest, though we also have a few Castilians and Qattaluni dotting our northern cities.

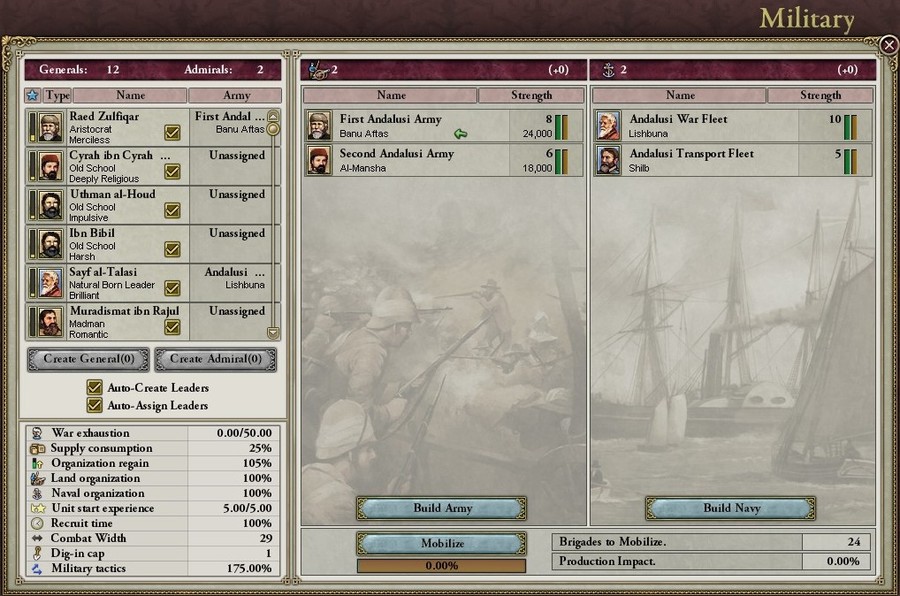

Moving on to our military situation, the Tirruni Wars has left us with a relatively small but well-trained and disciplined army, along with a plethora of generals and commanders produced by our finest military academies. The strength of the standing army currently amounts to 42,000 soldiers, but we can call upon another 72,000 conscripts if we’re in a desperate war, though only at great cost to our economy.

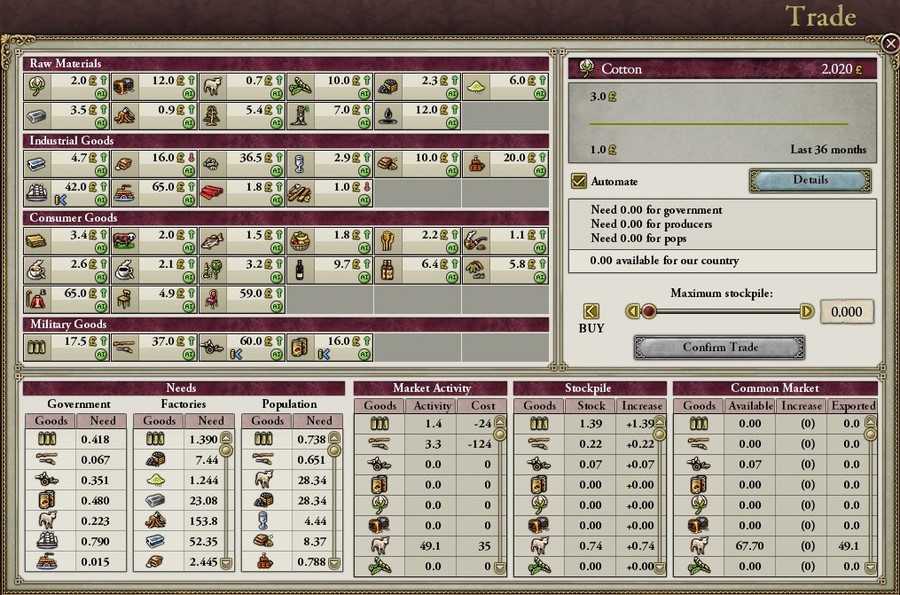

Speaking of the economy, we are largely an agrarian-pastoral country, with our three most-produced goods being fruit, wool and grain. There was also a great effort to construct manufactories during the waning days of the Jizrunid Sultanate, however, and these manufactories have persisted and now play an important part of our economy.

Our oldest manufactories are the steel factory in Tulaytullah, the winery in Granada and the small arms factory in Qadis - all built during the Jizrunid era. There was little further industrial development until the Tirruni Wars broke out, prompting the construction of ammunition and machine parts factories, as well as a clipper shipyard.

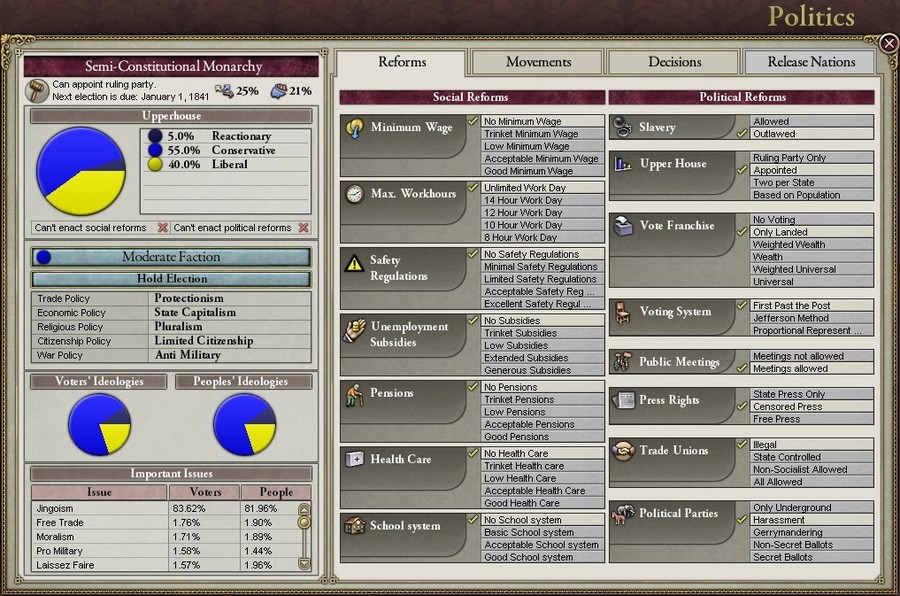

Another legacy of the Tirruni Wars is in our government: semi-constitutional monarchy. Whilst we do indeed have a constitution, much of the ruling powers still rest with the hereditary Majlis al-Shura, with the elected lower house restricted to purely advisory roles. The end of the wars also marked the restoration of monarchy after over fifty years of oligarchic rule under the nobles, as the widely-renowned Raed Zulfiqar is offered the crown and sceptre of Al Andalus.

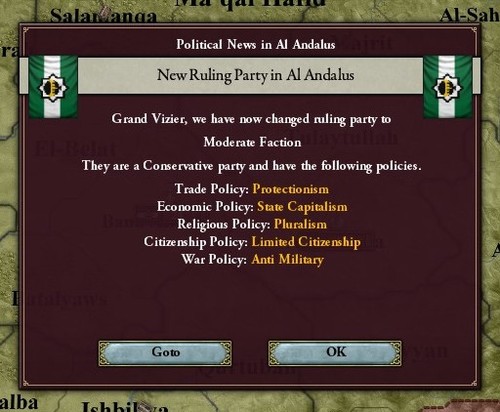

It was Raed who summoned the Majlis to form a new government early in 1836, and after a few half-hearted debates, it was the Moderates who emerged triumphant with a strong majority. Campaigning on a platform of peace and internal development, the moderates vowed to avoid any conflict throughout the next decade, much-needed after almost twenty years of constant war.

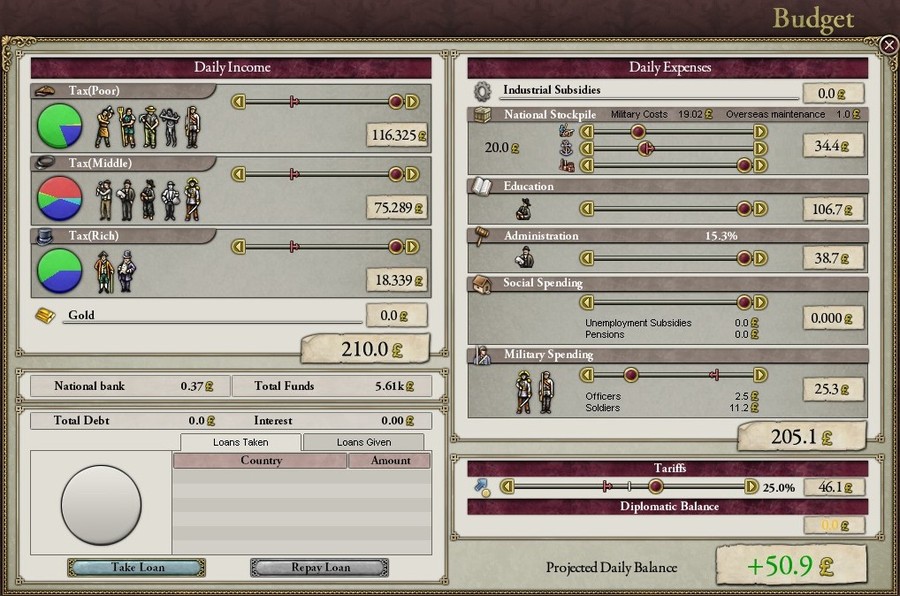

Once in power, the moderates quickly restructured the national budget, cutting military and naval funding in favour of education and administration. The costs of launching literacy programs and constructing new schools were very steep, however, so a harsh tax is levied on the populace of Al Andalus to keep us in the black.

Our standing army is currently stationed at Tulaytullah, under the supreme command of the veteran general Cyrah ibn Cyrah - now a very old, confused man. The composition of the force is a mess, however, and there will need to be significant investment into new artillery to bring it back up to scruff.

As for our seafaring forces, the Andalusi Navy enjoyed great success at the height of the Tirruni Wars, seizing control of the Straits and securing passage for an army to eventually sack Marrakesh. This stunning achievement was slightly tarnished when the Berbers retook Marrakesh and delivered a decisive defeat to the Andalusi Navy, but it is still a point of pride for all Andalusi.

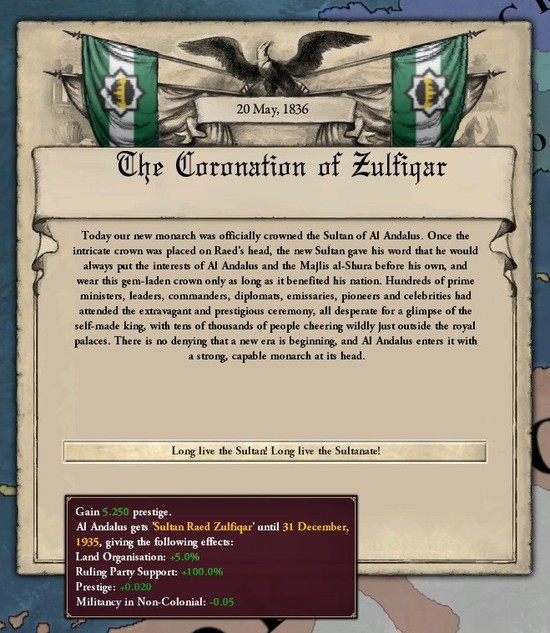

Shifting back to Qadis, meanwhile, the 20th of May became a day of celebration and revelry all across the city, with the festivities overflowing to the rest of Iberia before long. Raed Zulfiqar was finally crowned the Sultan of al-Andalus in an extravagant ceremony, attended by some of the most powerful royals and highest-ranking politicians in Europe, and the scene of the newly-minted gem-laden crown being lowered onto his head was forever immortalised in a thousand photographs and paintings.

With the ascendence of a new dynasty to the throne, the centuries-old flag of al-Andalus was finally abandoned, and in its place Sultan Raed adopted the Crowned Pomegranate - a symbol of unity between the new Sultan and the old Majlis. The golden colours associated with the Jizrunid dynasty were also discarded, with Raed choosing green for his dynastic colours.

(credit to clayren for the flag)

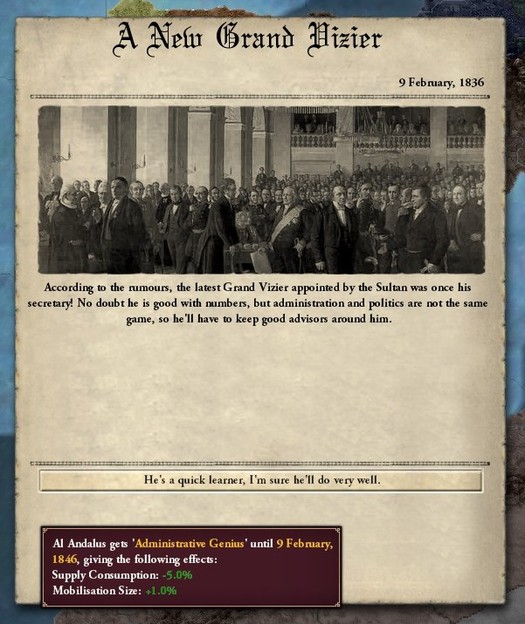

Now that he was Sultan, Raed could finally withdraw from political life, formally resigning from his position as Grand Vizier. The Majlis quickly met to appoint his successor, eventually deciding on a known moderate in Raed’s former secretary and closest aide.

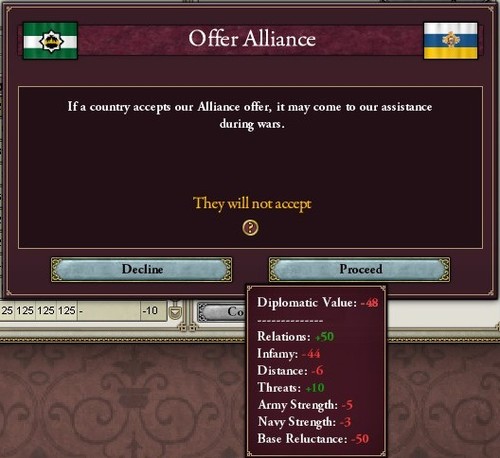

The new Grand Vizier immediately embarked on a mission to build an alliance network across Europe, approaching both France and Russia in the hope that their friendly relations could be formalised into an official alliance. Neither of them were interested, however, citing Andalusia’s unjust demands during the Congress of Cádiz upon turning our diplomats away.

The Grand Vizier had expected as much, however, and immediately set about further improving relations with both powers. And just in case the French and Russians remained stubborn, he adopted a policy of rapprochement with the other congress powers, dispatching diplomats to better relations with the Hanoverians, Serbians and Armenians.

At the same time, alliances were proclaimed between León-Castile, Qattalun and Morocco, likely as a precaution against Andalusi aggression. This would be a problem in the future, but there was still a four-year truce in place, so the Grand Vizier decided against further escalating the matter.

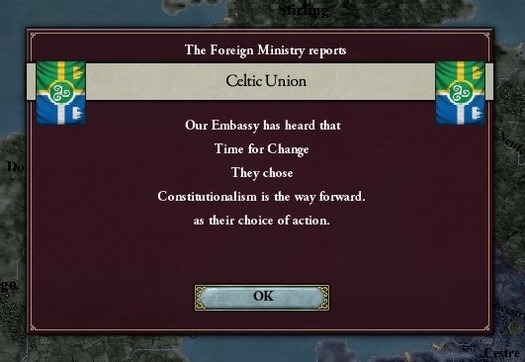

To the north, meanwhile, a new High King ascended to the throne of the Celtic Empire. And citing the urgent need for reform, this new king abandoned absolutism in favour of constitutionalism, proclaiming the formation of the Celtic Union.

Across the width of Europe, meanwhile, the newly-founded states of Outremer and Syria were off to an unstable start. Both powers immediately rivalled one another, and determined to squash any internal dissent, they began to oppress their religious minorities by restricting their rights, closing off their opportunities and driving them to emigrate.

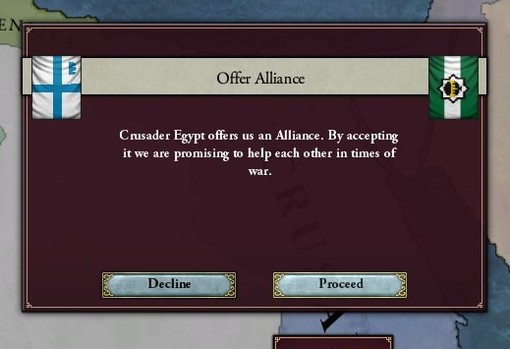

Further south, meanwhile, Andalusia’s policies bore fruit when the Egyptians dispatched diplomats to Qadis, hoping to form a defensive alliance against Morocco. Similarly eager for insurance against the Berbers, the Andalusi were quick to agree.

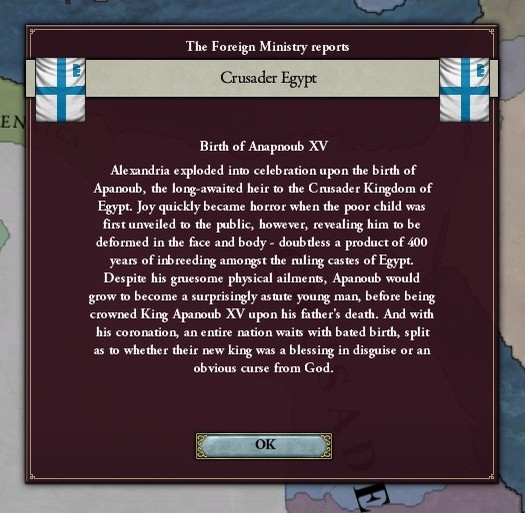

A scant few weeks later, Alexandria exploded into celebration as an heir was finally born to the elderly King Apanoub, ending the very-real threat of a dynastic crisis. Unfortunately, the happiness quickly soured when it was revealed that this prince was born with hideous physical deformities, an inevitable product of 400 years of inbreeding amongst the ruling castes of Egypt.

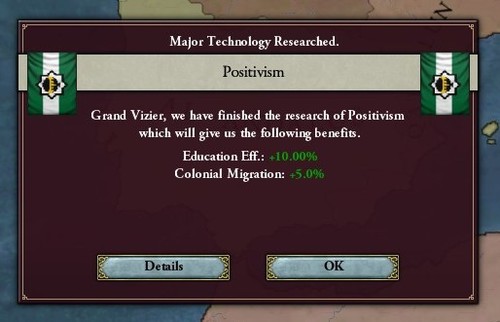

As stories of the monster-prince circulated Europe, the moderates made some advances on the educational front, as positivist thought is utilised in philosophical schools across Al Andalus.

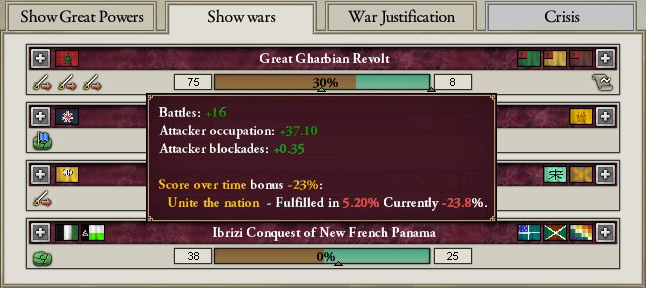

At the same time, across the chaotic and unruly Atlantic waves, the Great Gharbian Revolt was still raging with no end in sight. The Moroccans had managed to seize the upper hand, landing several armies on the northern coast of Imjir and gradually pushing south, eventually capturing the colonial capital of Port Almoravid.

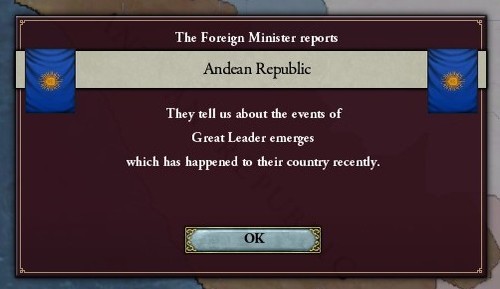

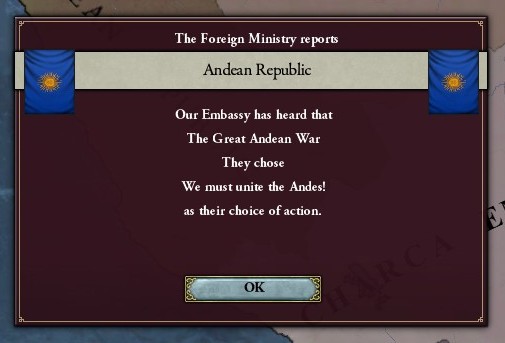

Further west, one of the leading Incan revolutionaries rose to power in the Andean Republic, the victor of its first popular election. And without delay, he turned his attention southward to the Charca Empire, with whom a heated rivalry had intensified over recent years, with the revolutionaries determined to overthrow the Charca emperor and unite the Andes.

And indeed, just a year into his term, a border demonstration exploded into full-blown battle as the Great Andean War finally broke out.

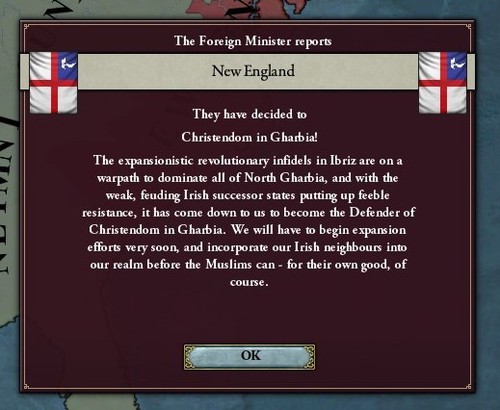

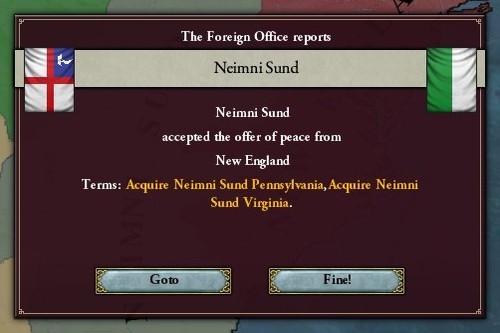

To the north, meanwhile, the Butler Queen of New England made a momentous announcement early in 1838. Declaring herself the Defender of Christendom in the West, she insisted that it was her ‘destiny’ to protect the fragile Irish states from the unfettered aggression of Revolutionary Ibriz - and what better way to do that, than by simply absorbing them?

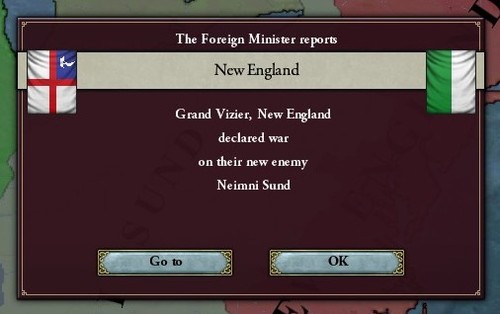

And so another war breaks out in northern Gharbia, with New England and Anbaila launching concurrent invasions into Neimni Sund from the east and west. Things aren’t looking good for Neimni Sund, and unless they manage to entice Ibriz into intervening, this may well be the beginning of the end for them.

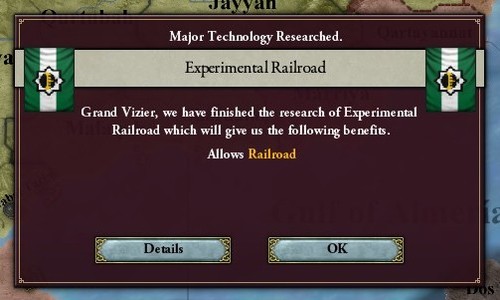

Back in Iberia, a revolutionary invention is made with the Experimental Railroad, horse-driven railway that allows the transport of metals, coal and other resources from their mines. The Majlis quickly authorises the construction of several miles worth of it, hoping to increase the output of the iron mines in Baja and Tulaytullah.

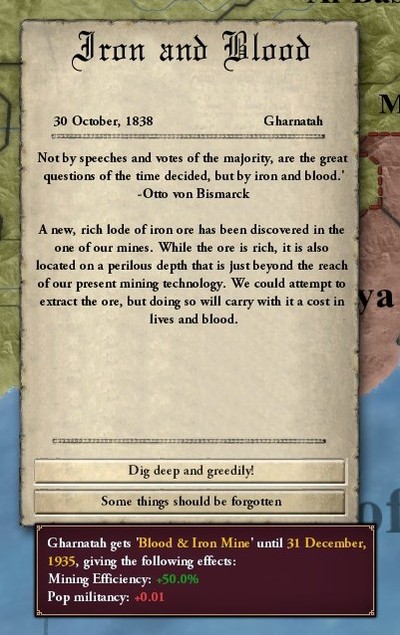

And just a month later, two miners stumble upon a rich lode of previously-undiscovered iron in one of our Granada mines. Workers are quickly sent to begin extracting the ore, and capitalists begin pondering the possibility of connecting Granada and Qadis by rail, massively cutting down on the time required to transport the iron.

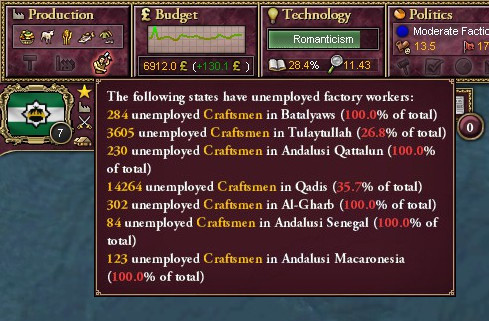

There isn’t much time to delve on the possibilities of railroads, however, as unemployment continues to rise throughout Al Andalus. Our current factories prove too few to meet the demands of our workers, and the large influx of soldiers returning home from the Tirruni Wars has only worsened the problem. The moderates thus begin to stockpile cash, reserving it for the construction of several new factories in Qadis and Tulaytullah.

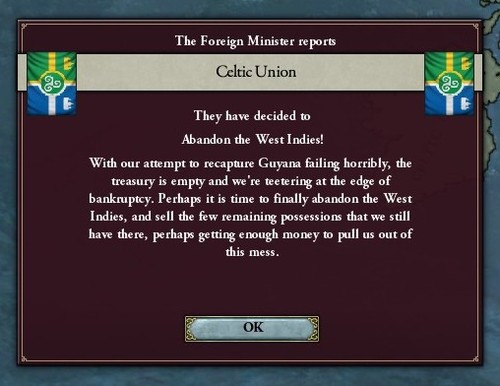

In the north, meanwhile, the Celts met with more humiliation as they failed in an ill-conceived attempt to retake their former colony Guyana. Not only was their invasion repelled, but it left the Celtic government bankrupt and in shambles, with workers’ riots becoming a weekly occurrence.

So in an attempt to claw their way back into the black, the Celts decided to abandon the West Indies altogether, offering to sell their few remaining possessions to several great powers.

Both France and Hannover refused the offer, and so the Celts turned to the Andalusi next, lowering their demands in a desperate attempt to get some money. The liberals in the Majlis immediately made their voices heard, and after several loud arguments and a short fistfight, the assembly agreed to pay the requested price and acquire the Leeward Antilles.

And with that, Al Andalus gains its first new colonies since the loss of Ibriz and Juzur Qarbiya - but would they will be built upon, or simply left to fester?

Sultan Raed didn’t care much, either way. He had abandoned politics altogether in favour of peace and quiet, only interrupted by the various court functions and necessary traditions. The Sultan also began sponsoring several governmental programs, throwing his weight behind the expansion of the University of Qadis, which would grow to accommodate thousands of new students by the end of the year.

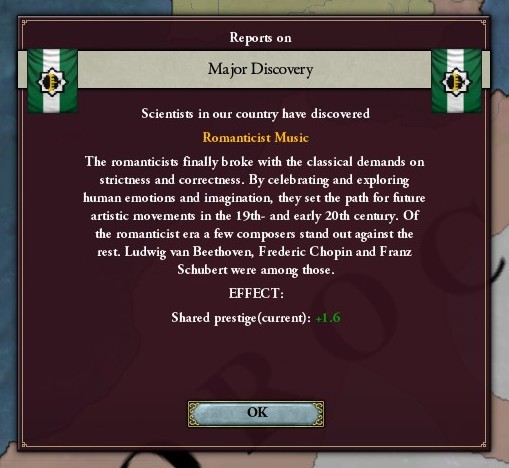

He also became the patron of a number of famous artists, musicians and writers, inviting them to ply their trade in his royal court in Qurtubah. Raed was particularly interested in the cultural movement that followed in the wake of the Tirruni Wars, known as Romanticism, which was characterised by the glorification of the distant past in favour of the destructive forces of modernity.

And there was no doubt that the modern world was a destructive one, with the Industrial Revolution spurring the invention of countless weapons of war. Morocco in particular had erected several new arms factories across the Maghreb, using them to produce long lines of artillery and guns, which were then shipped across the Atlantic and into the arms of soldiers.

1839 ended with a successful naval invasion for the Moroccans, seizing several beachheads in Nuquril and Walidrar. Imjir had launched a semi-successful counterattack and recaptured Port Almoravid, but the situation was looking increasingly futile for the Berber colonies.

Further north, meanwhile, the English-Neimni Sund War ended in a decisive victory for the former. The Irish were forced to concede vast tracts of land, and unless their prospects changed drastically, New England would be back for more before very long.

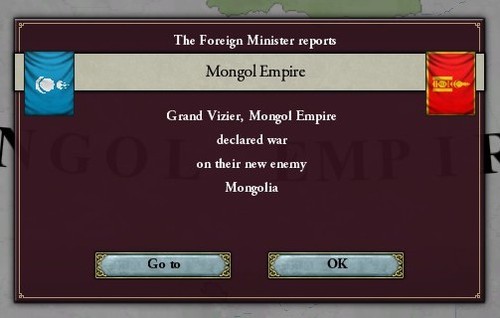

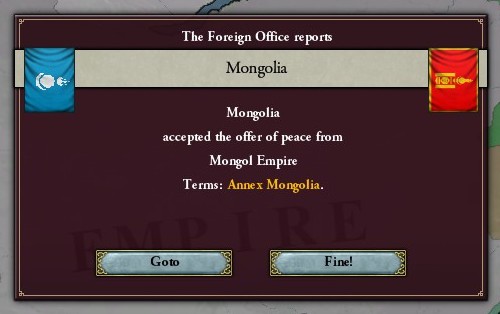

Across the choppy waters of the Pacific Ocean, meanwhile, East Asia had not exactly been stable these past few years. The Mongol Empire launched an invasion into Mongolia early in 1837, quickly crushing any opposition and seizing the major regional centres. And once victory was proclaimed, the great Migration-Conquest of the Mongols finally came to an end, having fought their way across Asia for the past 400 years and ending up right where they started.

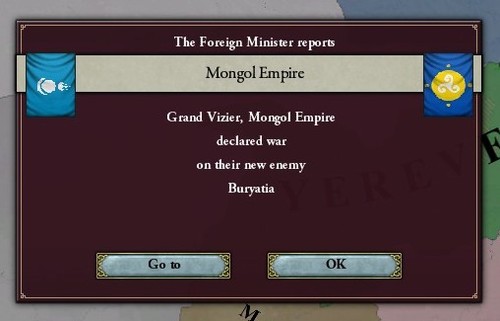

They weren’t going to lay down their guns just yet, however. The Mongols were determined to become the Emperors of China and Masters of East Asia, so they sparked a war with Buryatia a few months into 1838, looking to secure their borders.

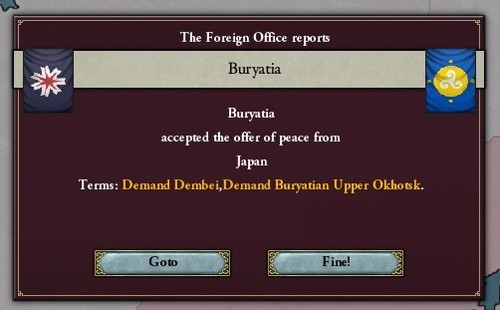

Unfortunately for them, this was a step too far for the Japanese, who were equally unwavering in their self-belief and determination to become the dominant power in East Asia. The Revolutionaries thus declared war on Buryatia, perhaps hoping to absorb them before the Mongols could annex the feudalistic state.

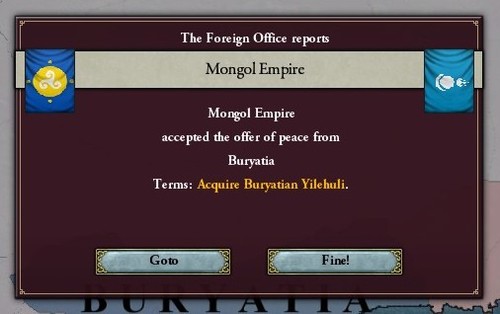

The two powers edged closer together over the course of 1839, and with war scares becoming more frequent, they finally decided to organise a conference and formally partition Buryatia. Japan thus annexed its eastern regions whilst the Mongols seized the west, with a small rump state left as a buffer between the two.

Whilst all this was going on, Yerevan managed to reunite the various Manchu khanates, and now served as another buffer state between Japan and Mongolia. Manchuria is far more valuable the icy wastelands of Buryatia, however, and this will undoubtedly become another hotly-contested region between the two Asian powers.

And as a new year approaches in 1840, another important day arrived as the truces agreed-upon at the Congress of Cádiz all expire. Few knew what to expect in the next few years, with theories and rumours and assumptions being thrown around, but they can all be reduced to a single question - will the peace hold?

Al Andalus knew what they would do, at the very least. The Moderates insisted that they would see the next five years out without any aggression, and instead focus on internal development, but can the same be said of the other congress powers?

1839 ends with some long-awaited triumphs for the moderates, as years of careful diplomacy finally results in the formation of a French-Andalusi alliance. And not long later, emissaries arrive from Provence offering the same, which the moderates quickly agree to.

So as the first days of 1840 begin, Al Andalus can finally begin to look to the future with hope. Peace has reigned for five years, new colonies have been acquired for the first time in centuries, experimental railroads and new factories are in the process of being constructed - things are certainly beginning to look up for the Andalusi.

And their place amongst the Great Powers cannot be doubted any longer. We can’t go tit-for-tat with them on the battlefield just yet, but we’ve laid the foundations for a strong alliance network, and our prestige and industry is up there with the best of them.

Unfortunately, however, this string of success comes to a screeching halt early into the year.

Raed Zulfiqar has finally left the world at the ripe old age of 71. Born to a minor noble family of scarce means, Raed’s early life was difficult and unstable, but he finally began to fulfil his potential upon joining the military and quickly rising through its ranks. Before long he was named a commander, and after several successful campaigns he managed to seize power of the army, forcing the Majlis to declare him their Grand Vizier.

Worrying beginnings, maybe, but nobody can deny that Raed had bled for his country. He led the invasion of the Mahdiyyah, he fought against the Berbers for near two decades, he oversaw the Moroccan Campaign and Sack of Marrakesh, and he reunited Iberia after seventy years of hurt and division. There is no doubt that when he finally got his crown, he was fully deserving of it.

He came into the world a nobody, and leaves it a king.

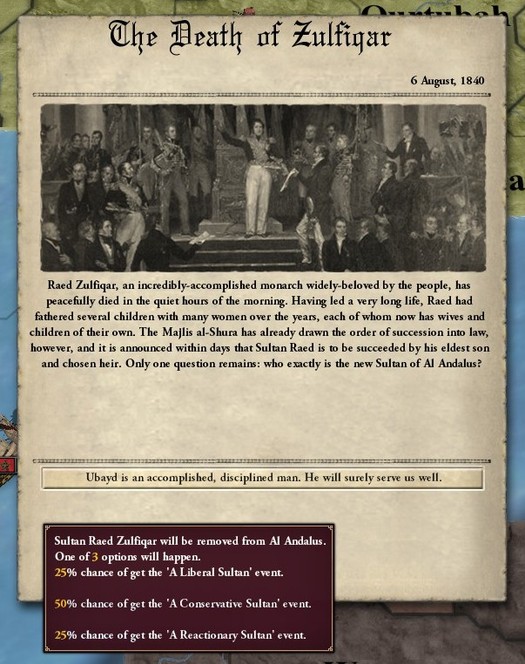

As the great man is lowered into the ground, however, the world’s attention flits to his son and successor. What kind of sultan will he become, and what course will he set Al Andalus upon?

World map: